I am Aubrielle Weaver, spending my summer in San Diego, California, at San Diego State University (SDSU). For the next six weeks, I will be studying microbiology. My mentor is Gregory Burkeen, who is a Ph.D. student at SDSU. This is week 1 of my internship.

My first day wasn’t until Tuesday, June 20th, because of Juneteenth. My goals for this internship are to isolate and identify bacteria and phages. By doing these tasks in the next six weeks, I will learn basic lab skills to prepare me for science courses in college and the career I want to have.

On the first day, I started the process of isolating bacteria from Kefir. For those who do not know what Kefir is (I didn’t either until this week), it’s a fermented milk drink, almost like yogurt. We needed to create an agar plate with a milk medium to grow this bacteria.

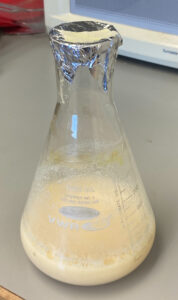

An agar plate is a petri dish filled with a solidified liquid that provides nutrients to bacteria. You can make many types of these. However, Greg had me do a very simple one. We took 30 grams of powdered milk and added water to create 300 ml of milk in a flask. We then took 4.5 grams of agarose powder, which is a lot like gelatin, and added it to our milk. Once sterilized and poured into Petri dishes, it will solidify into a soft gel that will support bacteria growth.

A ph factor dye was added to ensure the milk wasn’t too acidic for bacteria to grow. When this dye turns yellow, it means acidic. A reddish-orange means neutral. And a magenta-pink color means basic. The stain determined it was a little too acidic. Greg added sodium hydroxide. This made the milk gel safer for bacteria.

Finally, I covered the flask with aluminum. I labeled it and placed it in a bin with a little bit of water in it. We then took our milk mixture to the autoclave. An autoclave is essentially a pressure cooker. Once something is sealed in, the pressure is increased so that the liquid can reach a high temperature without boiling over. Often the temperature needed to kill microbes is higher than the boiling temperature at standard pressure. While waiting for it to sterilize, I read some materials Greg had given me.

Once it was done, we slowly let the temperature decrease to 95 degrees Celsius. The milk would boil if we opened it up while it was still at a high temperature. Once it cooled down enough so it wouldn’t warp the Petri plates, Greg showed me how to pour it. To fill them, I had to turn on a Bunsen burner to keep the air flowing and push airborne microbes away from settling in our milk. In addition to the burner, I had to hold the flask at an angle to decrease the surface area microbes could land on. To keep the dishes sanitary, you had to keep the lids on until you poured them and then put them back on. The only bacteria we want in our dishes are from the Kefir. That is why we went through the whole process of the autoclave, bunsen burner, angling the flask, and having the dishes not open for long. We set them out to solidify.

I could tell they were solid when I saw a slight wrinkle on the surface. I flipped them over and propped them slightly open on their lids to let them dry near the Bunsen burner.

Setting them upside down prevents microbes from landing on them. Greg showed me how to spread the Kefir samples from the Caucasus onto a dish when they were dry. I then did the same with the Spain Kefir on one plate. Then we left the two plates with their lids on to let the bacteria grow. For the rest of the day, I took notes from a textbook about microbiology.

No growth was on my plate when I came in the next day. The room temperature was a little too cold for the bacteria. I put the bacteria in an incubator to promote growth. Then I started researching different tests I could run to identify the bacteria. I will be doing these tests later.

When I came in on Thursday, Greg and I checked the two plates. And there wasn’t any growth. Greg explained this could mean two things. One that the bacteria grows slowly on this media. Or that the media is missing something the bacteria needs to grow. So we started a positive control and a test plate. From earlier tests, Greg knew that the bacteria, L. rhamnosus, grows on a media called S. thermophilus. It was our positive control. I observed as he streaked a bacteria sample onto the positive control media and the milk media I had made. We put them into an incubator at 42 degrees Celsius. The higher temperature will cause the bacteria to grow faster. These results determined my next step.

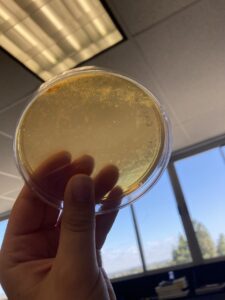

The following day I came in, and immediately, Greg told me there was good news. He had checked the positive control and test plates. The test plate had bacteria growth!

This determined that my media was suitable. We then went to check my plates that started on my first day. And one of them had growth too. My next task was to look at the original plate with growth. I needed to determine how many morphologies there were on the plate. Morphology is a bacteria’s size, shape, color, and texture. It’s a way of determining how many bacteria you have on your plates. Bacteria from one colony will all look the same. (Besides slight variations in size). My original guess was four morphologies.

Greg showed me how to collect a sample of the tiniest bacteria morphology and streak it onto another milk agar plate. I then did the same for the other three morphologies onto three new milk plates. He then showed me how to streak from a liquid sample of bacteria. And I replicated what he did. We then set the six new plates in the 30-degree Celsius incubator with my original two bacteria plates. We might be able to see new morphologies from my original plates.

Then Greg gave me a recipe to make Streptococcus Thermophilus media in liquid and solid form. You don’t add agarose powder to keep it in liquid form. We put them into the autoclave to sterilize. I will use the liquid form later, but I poured the solid version into the plates. The goal of pouring is to pour just enough to cover the bottom of the plate. Once they were poured and solidified, I left for the day.

On Saturday, my roommates at the Airbnb and I went to the beach to swim. And later we went to a cliff area to watch the sunset. Then Sunday was a relaxing day. I finished this blog, did some summer homework, and read the microbiology textbook more.

I quickly adapted to driving in San Diego and look forward to five more weeks in this beautiful weather.

There are no comments published yet.