My third week in the field entailed working in and around the Gunnison area. A new field crew composed of graduate students studying various aspects of evolutionary biology at a Colorado University joined us. We reconvened her the summit Cochetopa Pass, an esoteric lovely part of central Colorado with these new field biologists and began our work promptly. Each of these students have their own research project yet they converge to work with us on the trapping efforts. They were all extremely engaging and it was fascinating to learn of their individual efforts at unraveling secrets of evolutionary biology.

My third week in the field entailed working in and around the Gunnison area. A new field crew composed of graduate students studying various aspects of evolutionary biology at a Colorado University joined us. We reconvened her the summit Cochetopa Pass, an esoteric lovely part of central Colorado with these new field biologists and began our work promptly. Each of these students have their own research project yet they converge to work with us on the trapping efforts. They were all extremely engaging and it was fascinating to learn of their individual efforts at unraveling secrets of evolutionary biology.

One of the students is currently studying barn swallows and their genetic diversity in the state of Colorado similar to the Sean’s work- only with the barn swallow. There was a botanist student searching for native plants in the area and entering the data in a vast inventory similar to the Heritage Project employed by The Nature Conservancy. Spending evenings making dinners together was a bonus as I was able to engage with these students and learn about their field work as well as their aspirations in their field of study. This is particularly important to me at this stage in high school as I get ready to embark on my own studies and I now have a better idea of the type of work that is entailed in field studies and then laboratory work and calculations and interpretations!

I also was intrigued how each of the students became interested in the species that they had decided to devote four plus years of their lives to studying. These college students are currently enrolled in E-Bio classes were able to give me insight on how to maximize efficiency in college as well as the difficulty of balancing labs with athletics and other classes.

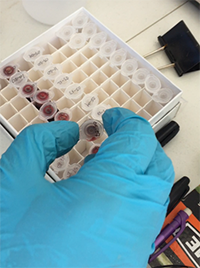

Almost every day this week we would get up at 4:30-5:00 AM to set around 70 traps, fill them with grain, and then return to the site after a two-and-a-half hour interim. Since we are nearing the end of the data collection period, we are preparing for genetic analysis of the hundreds of prairie dog blood samples we’ve taken, as well as the flea species that have the prairie dog as their host.

This analysis will be performed using centrifuge, which separates DNA into layers. The mitochondrial DNA can then be removed and analyzed, and samples sent to a professional lab to be sequenced. The main purpose of this process is to identify particular species of fleas, and to determine which species of fleas are found on which groups or species of prairie dogs. Further analysis is then done on the samples of DNA collected from the trapped prairie dogs in an effort to decode the DNA and determine whether or not the colony has speciated, and whether the prairie dogs have bubonic plague or not.

DNA can then be removed and analyzed, and samples sent to a professional lab to be sequenced. The main purpose of this process is to identify particular species of fleas, and to determine which species of fleas are found on which groups or species of prairie dogs. Further analysis is then done on the samples of DNA collected from the trapped prairie dogs in an effort to decode the DNA and determine whether or not the colony has speciated, and whether the prairie dogs have bubonic plague or not.

Bubonic plague can be carried by prairie dogs, however, if a prairie dog colony becomes infected with the plague they are nearly 100 percent non-immune and there will be a high level of mortality. The plague is caused by a bacteria (Yersinia pestis) that resides in flea. Prairie dogs are considered to be host vectors of the plague as are many other mammalian species from small rodents to larger ungulates like elk and deer.

The study has several objectives and finding out which species of flea live on the various colonies of prairie dogs is one aspect. Further interpretation of the flea DNA data may help to unravel whether one particular species of flea is more prevalent, and also whether one species of flea may be more likely to be a host of the Yersinia bacteria.

Of course of main importance of this study is to continue to obtain as many samples as possible in order to have a larger sample size to increase the statistical integrity of the study. With these large sample sizes, the genetic divergence of populations will then be determined, which will be key to how and where one species becomes another, geographically.

There are no comments published yet.